Studio Visit: Christina Corfield

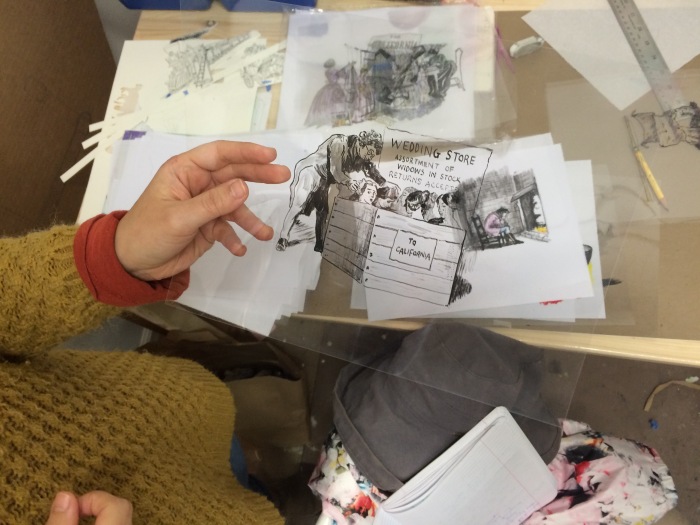

There’s a question I’ve been wanting to ask Christina Corfield for a long time. Her well developed studio practice might be described as a kind of handmade history of culture and technology. Corfield’s signature practice consists of deeply researched historical narratives, elaborate theatrical sets made of cardboard cut-outs, and non-professional actors performing before her camera. Her exhibitions often redeploy pre-cinematic forms of visual narrative such as the tableau vivant or magic lantern. She is currently painting on circular transparencies and animating the images in homage to praxinoscope. After achieving the effects she desires on video, Corfield destroys or reuses the materials so that the video-taped scenes displayed in her novel gallery exhibitions are all that remain of her thought provoking re-performances of history. I recently visited Christina in her Oakland, California studio where she is at work on several projects. Ghosts in the Shell tells the story of the first “computers,” female mathematicians whose job was to compute complex mathematical problems. Her ambitious work-in-progress on The Pony Express departs from her recent focus on female centered histories of technology to explore the myths of the American west.

k: [Laughing] You don’t seem like a fucked-up person, but your work is fucked-up. How has the theme of sexual violence developed in your work?

[Also laughing] You’re going to have to be patient as I think about this. It’s not that I feel uncomfortable talking about it, it’s that I genuinely haven’t thought about it. [There is a pause.] It’s almost kind of a question: In our society, in our culture, what are the techniques that allow us to talk about difficult topics? That’s what the starting response would be. Beyond that, certainly [in past work] I was thinking about the ways in which we’re enculturated to fairytales. Weird childhood safe images, cute images, or pretty images. Stuffed animals. It is like a mishmash of images that I saw in fairytale books as a kid. In a way it is trying to juxtapose something really seductive and beautiful with something really problematic. Trying to find the line where you cross from really enjoying having the experience of visual pleasure—and where you reach a point where you’re like, “Oh-no!” What do you think when you get to that point? Do you stay in that point of, “the dress is really pretty,” or do you think, “Oh shit, that just had that cut off by that.” It is about lines of acceptance, or tolerance, or pleasure in our culture. That’s what I’m playing with. Certainly with the cardboard cut-outs–I paint them realistically and I have actors with the the cut-outs–one layer is more real than the other. All these different layers of “What is more real? What is realism in this picture?” There are lots of different layers to that.

It is all about drawing a line. Is there a line? Can we find that line? So again, definitely: the limits of things. The type of work I make—because it looks the way it does—it can be read like it is just silly or fun. I think there are a lot of unknowns. I’ve always been really interested in myth. Myths and semiotics: put these symbols together and you’ll produce a myth. I’ve fine tuned the specific types of myths I’m interested in. The narrative of the woman, the feminist narrative, that took me awhile to get to and it took me awhile to call it that. I’ve always had an interest in having a main character who is a woman and usually that narrative is pretty unforgiving of the woman’s woman-ness. The Pony Express project does not have a woman at the center, it’s really a masculinity project. That needs to be taken down. What’s the deal with that? [The way the American West is] dramatized, emotionalized, heroicized verses what it really was. [I’m interested in] canonical myths—in taking their canonical power away.

k: What is the question you most wish someone would ask you about your work?

cc: A question I would be interested in asking other artists is: What gives you visual pleasure? What is craft to you? How important is it that you make something with your hands? Why? And why don’t you? What does work like this do to you? When you see work like this what do you do? Do you dismiss it or do you take seriously? Why and why not?

Visual pleasure is really important to me. Craft is really important to me. There’s something about making stuff with your own hands, painting things, asking—does that look real enough for me? Should I put more brown on that?—quite traditional aesthetic questions. There’s a real joy in the materiality of the props that I make. The narcissist in me says “that’s mine! I made it!” Authorship, definitely authorship. But it is always balanced with the performances of the actors. In as much as I tell them what to do, I’m also open, it’s a kind of collaborative thing. Even thought they’re not professional actors there’s always a certain amount of flexibility, I’m not going to tell them how to say their lines. If they want to set something up differently I’m open to it. But with my artwork, I’m kind of a control freak. I really know what I want. By the time I’m filming things I know what I want. The power of visual pleasure to allow us to talk about difficult things is important to me. I would say that’s probably my central theme. This, this is my visual pleasure. This is what I like to see. When I see work that looks like this that other people made, I get so excited! And it’s out there, there’s not that much of it but it’s out there. In the last few years I’ve been wanting to go back to shitty cameras and produce images that are dirty and not clear. I use the F-3 and its beautiful and it makes absolutely gorgeous images but there’s a part of me that thinks, “when you’re surrounded by that all the time does it really have power anymore?” I definitely have this push against the perfect, the perfect image, the perfect technique.

Christina Corfield is an award-winning Oakland based visual artist. She was born and raised in [City], United Kingdom. Her work has been exhibited in galleries throughout the United States and the UK and reviewed in publications from The Glasgow Herald to The Huffington Post. She holds an MFA from San Francisco Art Institute and is currently pursuing a PhD in the practice based Film + Digital Media program at University of California Santa Cruz.

http://tinacorfield.com